I was only going to correct my last email because even though I have a GPA of 4.0 as a physics undergrad, I do not know the difference between 6 and 9. My show is not on the 16th. It is on the 19th.

Wednesday, June 19, 7pm

Yonder: Southern Cocktails and Brew

114 W King Street

Hillsborough NC 27278

However, since I’ve got you here, I might as well tell you another story about humility — someone else’s this time — and why music makes you feel things.

A few months ago, to my surprise, I explained something about physics to physicist and bestselling author Sean Carroll. Sean really didn’t know and was grateful for the explanation.

He periodically asks his patrons for questions and then answers them in an “ask me anything” podcast. The questions range from existential to cosmological. Sometimes, the podcasts are 4 hours long; I always think there’s no way I’ll listen to the whole thing. Then I do.

Someone asked Sean if there was a physical explanation for how music makes us feel. Why, for example, do different combinations of notes — physical phenomena with mathematical relationships, after all — sound sad, bright, or mysterious?

Dr. Carroll was humble enough to read the question and admit he had no answer. I don’t have a complete answer, but I know in which direction the answer lies, so I sent him a message. His response was equally modest and a reminder that science is humbling, or should be, even to the most accomplished. The biggest tell of a crackpot is unassailable confidence in their ideas.

Of course, our cultural background and personal history strongly affect how we feel about what we hear. However, there are some physical realities in music that, at the very least, compel us to feel something. One of my favorites is the phenomenon Western music theory calls the minor chord.

Think of the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony or Ain’t No Sunshine by Bill Withers. There’s darkness and tension. How you interpret it is largely a result of your cultural training, but the tension is there. To understand why, all you need is grade school math.

Thousands of years ago, people knew that if you make a note at exactly half the length of a lyre string, it is an octave — a note that is obviously higher but also sounds like the same note. If an A vibrates 440 times per second, there are also As that vibrate at 220 and 880. You can theoretically halve and double that frequency all you want, and you’ll have a note that sounds the same but is different.

Here’s where more exciting things start to happen. What if we add the original 440 to 880? At 1320, we get what’s called a fifth. Do re mi fa so. One, two, three, four, five. The first two notes of Also Sprach Zarathustra by Richard Strauss — the intro music to 2001: A Space Odyssey — are the “do” and the “so,” the first and fifth notes of a Western scale.

There is not much emotional information between these two notes. In Strauss’s piece, you may notice that it feels like we’re waiting for something to happen until the first three notes give way to two dramatic chords. The first and fifth notes of the scale are so closely related mathematically that their relationship is only slightly interesting, like a couple who wear the same t-shirt.

We need to keep going up this series of overtones — literally tones over the tone — to understand the tension in a minor chord. After the octave and the fifth is another, higher octave — we add another 440 to 1320 and get 1760, which is also 440 times 4, two octaves higher than our original A note. 440 x 2 = 880, 880 x 2 = 1760.

What happens if we add another 440 vibrations per second? At 2200, suddenly, we seem to get emotional information. This is the major third. Do re mi. Do and mi are the first and third notes.

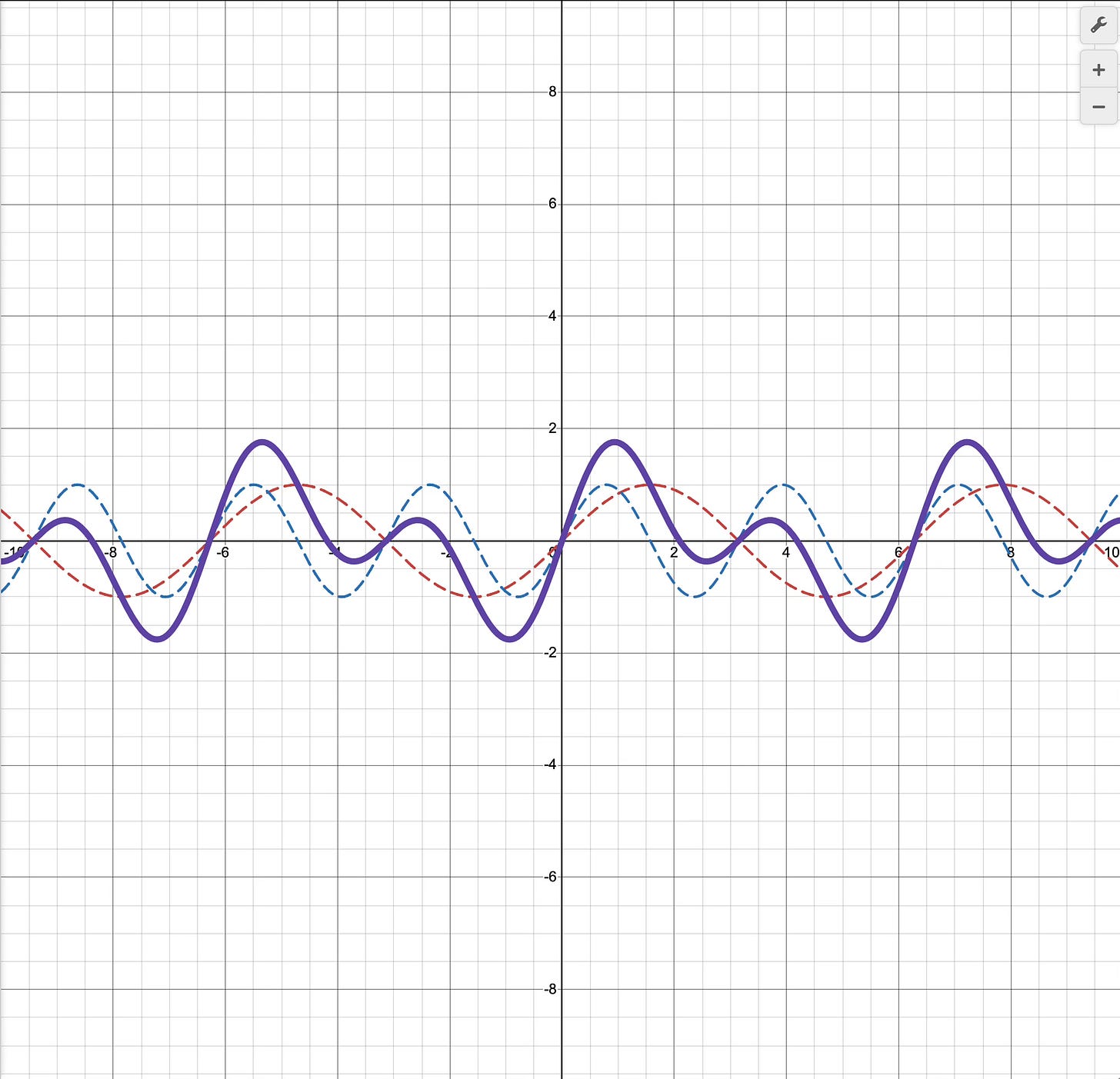

If you think about different kinds of waves in a wave pool, some long and slow, and some short and fast, you can imagine how the peaks might add together in places or how a peak and a trough might cancel each other out in other places. The third is the first note of the harmonic series that seems to introduce a compelling amount of chaos into the wave pool. Peaks start to break and fold. Our brains go, hmmm.

All of these intervals are present in every note of any non-synthetic instrument. Any natural vibration will create a distinct harmonic series. We can say things like, “The fifth of the third is the seventh of the root.” Doesn’t that sound complicated? It is, and we love the sound of all those vibrations dancing in our extraordinary ears. If I play an open A string on a guitar, the octave, the fifth, and more are a part of the unique character of that note. This fingerprint of overtones is part of what makes a flute sound different from a trumpet. Throat singers take advantage of the situation and emphasize the overtones, clearly producing two or more notes. Barbershop quartets will combine their notes to create virtual high notes that no one in the group is actually singing.

However, there’s another third in Western music. Some cultures have several. The one we’re concerned with is a little lower than a major third, and it is why a minor chord contains so much emotional tension.

When I play an A at 440, the major third at 2200 (C#) is already present in the harmonic series of that note. It’s just a mathematical resonance. When I play the minor third, a C, around 525, 1050, or 2100 vibrations per second, all hell breaks loose in the wave pool. None of the frequencies or their harmonics play well together.

But who doesn’t love a handsome villain or a good cry? The minor chord defies our tendency to categorize emotional information however hard we try. Like most choices of the heart, it’s a moving target.

So, is the emotional quality of music cultural or physical? Yes. Yes, it is.

Speaking of feelings, it sure did feel good to teach something to someone who has taught me so much. Sean Carroll’s podcast is called Mindscape. You don’t have to be a physicist to listen. There is no math, and not all the questions have answers.

That reminds me of what a polite and exasperated rabbi said to my friend’s son. “Your questions are so good. Are you sure you want to trade them for answers?”

I am sure I’m playing on Wednesday, June 19th. There will be minor chords.

“Sad songs say so much.” — Bernie Taupin

Your fan,

Jonathan Byrd

Share this post