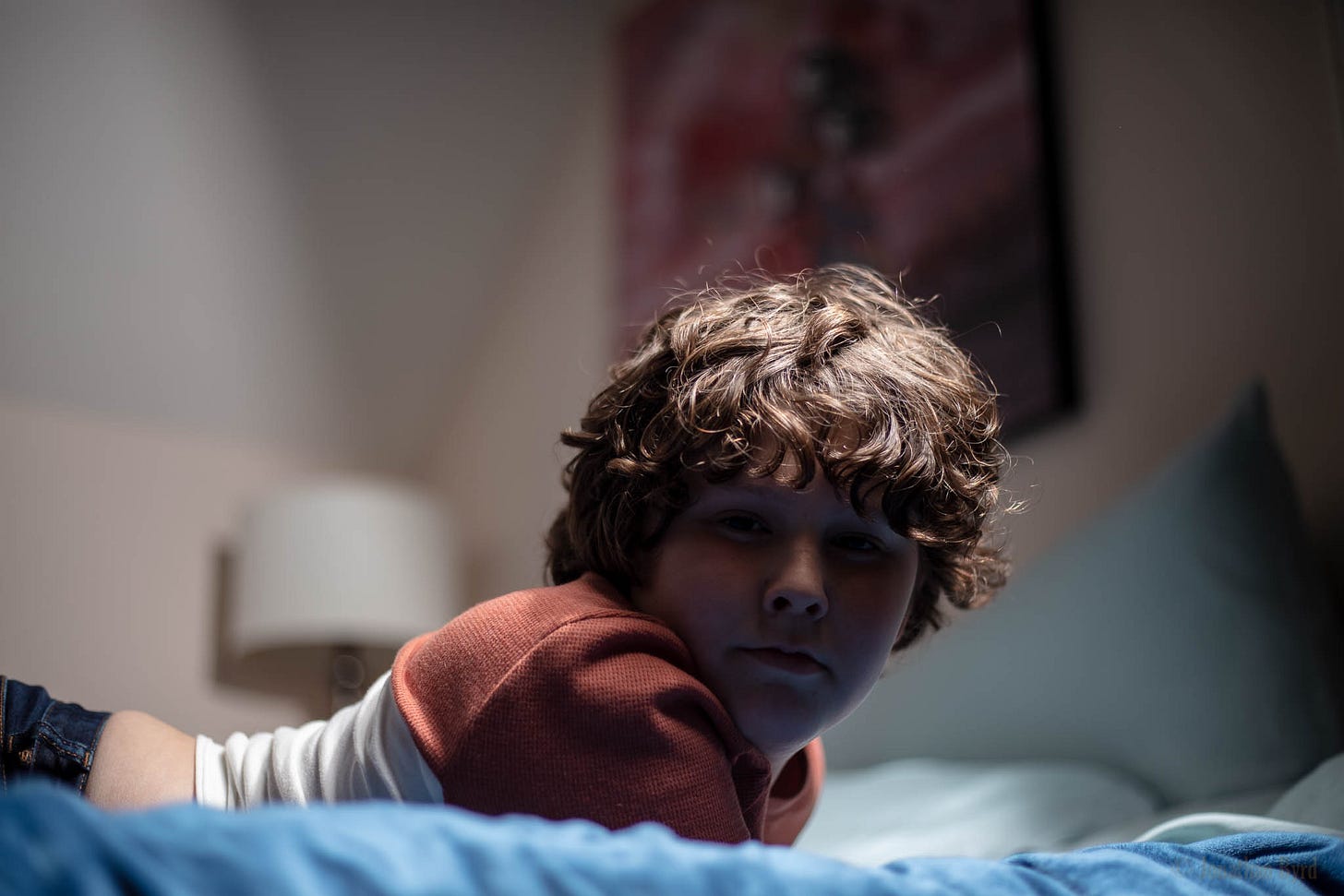

I pulled my 13-year-old son out of school last December. He tried very hard for seven years. He became defined by everything he wasn’t good at. I knew he was smart. I knew it wasn’t his fault.

I registered a homeschool with the state, “The Parker-Morales Homeschool,” named after Peter Parker and Miles Morales, his favorite Spider-Men. As Corin Raymond says, “the Charlie Brown of superheroes.”

He came home and played video games for about 8 months. I didn’t teach him anything. I called a friend and we built a gaming PC from parts. He mowed my mom’s lawn for money to buy games. I paid him $10 apiece to do piano lessons with an app — don’t judge me. It’s cheaper than a teacher, and he can play Stand By Me.

In fact, this whole thing is about not judging me or my kid. Or anybody’s kids.

I had rules. In bed by midnight, get up whenever you want. Make your bed. Take your medicine. Therapy once a week.

Maybe I’m trying to repair my trauma, and maybe that’s okay. By the 4th grade, school was an endless nightmare for me. No one knew about gluten intolerance, and ADHD was called laziness. By high school, I was running around and hiding under the bus until everyone had gone inside, then running off into the woods, buying lunch at Hardees with $20 stolen from my dad’s wallet while he was passed out drunk, making my way slowly home so I was there when I was supposed to be.

I have a photographic memory. It doesn’t work like in the movies, but I don’t forget numbers. My first-grade spelling teacher gave me books to read while she taught the class. I learned a lot of math by stick-building houses with my dad for Jim Walter Homes. I read everything. I was smart and curious, but I barely graduated high school, disillusioned and angry at having been forced to do it. I joined the Navy and started on a tank landing ship as a deck seaman. I saw a job I wanted to do — maintaining and operating the CWIS system, a radar-controlled Gatling gun that fired 3000 rounds per minute and turned an incoming missile to confetti. I learned electrical theory and Boolean algebra while working 12-hour days and rotating night watches, took a test, made the rate, and skipped two years of school normally required for that job.

This is how I know my son is not lazy or stupid.

He’ll spend 80 hours or more “platinum-ing” a game, meaning he has completed the main mission and all the side quests, and collected every little hidden thing in every dark corner of the game. Then he’ll go back and explore. He’ll go on YouTube and learn how to mod the game. He’ll learn the history and lore of the game, the company that released it, the team that created it, the voice actors, composers — should we call that “diamond-ing”?

Whatever it is, I recognized myself in it. I remembered hitting the rewind button on a cassette player thousands of times and learning every note of Joe Satriani’s “Surfing With The Alien” on guitar strings so old they should have given me tetanus. More recently, I was diagnosed and started taking medicine. I’ll never forget having a conversation with a friend that first day. An hour in, I started crying uncontrollably. This is what it felt like to be present.

The medicine didn’t fix me. It gave me a ladder with which to reach the shelf.

I practiced executive skills. I made lists and didn’t lose them. I forgave myself for everything.

My girlfriend, probably tired of hearing me talk about the latest physics news all the time, said, “Why don’t you take a class at the community college?” I was terrified, but I was curious. Did my new superpowers — or were they normalpowers? — extend to a classroom? I went and applied.

Long story short, I’ve been accepted into a baccalaureate physics program at NC State. My GPA in high school was 1.8. My GPA in college is 4.0. I’ve got a long way to go, but I’ve already learned the most amazing thing I’ll ever learn — I can do it.

My son is happy now. He’s a fantastic cook. He texts me kissy faces.

As the new school year approached this summer, I asked him what he wanted to learn. He took a standardized test, and we got an idea of where he was compared to his peers. His reading and word comprehension is college-level. His writing is appropriate for his age group. His math skills are behind, so we went back to decimals and fractions. I got a white board for our living room. We do a little every day.

My uncle Rodney called and said he’d a lady named Katie who works with the North Carolina School of Science and Math. It’s a boarding high school for gifted kids from across the state, and part of the UNC system. Teenage Einsteins and Curies walk the campus in black eye shadow and Zelda t-shirts.

He suggested I call Katie and talk about my son’s journey. I was leery of taking advice from anyone in the public school system, but we met for coffee. After telling her everything, Katie did the one thing I did not expect. She told me I was a great father.

Katie took the time to visit the local junior high with us, where my son would go to school this year, if he decided to go to school. The principal met us in the lobby and gave us a tour, talking up the teachers and programs. I asked the principal where his daughters went to school. They go to a private school. So, yeah, no.

Katie also mentioned there was a robot club at the North Carolina School of Science and Math, and you didn’t have to go to school there to join the club. They build robots and compete against other robot clubs in robot games. Rowan wasn’t quite old enough — it was supposed to be for high school students — but she’d ask if it was okay for us to come to the introductory meeting.

They said we could come. Katie met us there and introduced us to everyone. It was free to join, and money would never be an issue. If you needed a laptop or field trip money, they would find it. No one mentioned his age. Some kids wrote code. Some built parts. Some worked on outreach. Everyone was respected and included. The kids ran the entire presentation.

My son said he didn’t think it was for him. He said, “I thought we were homeschooling. Please don’t make me do this.” I knew I was going to make him do it.

I said, “Look. This is an incredible opportunity.”

“Why does everybody always say that about everything?”

“Right. You’re right. But here’s the thing. You don’t have to be good at this. It’s not school. It’s a club. Just show up and help them build a robot. If you’re not good enough, they’ll kick you out. But I don’t think that’s going to happen. I think you’re going to love this. Not like, someday when you’re older you’ll look back and say you’re glad I made you do it. No. Like, in a few months, you’ll be really grateful that you’re here. These are your people.”

“I don’t know, Dad.”

I did.

This past Monday, we went to our first club meeting. They asked him what he wanted to do. He chose the mechanical team. We walked over to that lab and sat down with a group. The team leaders talked about various choices they had to make when building the robot. Would it have treads like a tank, or wheels like a car? They went around and asked everyone their opinion. At the end, we circled up. Everyone, mentors and students, said their name, their preferred pronouns, and one thing they learned that evening. He said he learned that “I should always have some blank sheets of paper.”

When we walked out, he said, “Dad. I want to go here every night. I want to go to this school so I can walk out of my dorm and go to that lab.”

I did not say, “I told you so.” Not exactly, anyway. Not right away. I did hug him. I might have cried a little bit.

A few nights later, he learned CAD software. He showed his mentor what he’d done, and the mentor said, “Oh. You’re way ahead of us. We haven’t gotten to 3-D yet.” He came home and showed me how to make a 3-dimensional stop sign in OnShape. Then he learned how to draw shapes on the sign while I watched, and in a few minutes, it said “St0p.”

It was a hexagon. We’re still working on math.

Thanks for the ladder, Katie.

Monday evening, we’re flying to Scotland for ten days. Technically, he’s required to be at robot club at least one night a week. They said, “We’ll work around it. Not a problem.”

Thanks for the ladder, robot club.

All my fans, readers, and students — you believed in me years before I honestly believed in myself. Thank you for the ladder.

Share this post