The Way To Keep Going

— let go.

I can’t tell you why or how I make things. That’s why I make them.

Years ago, I wondered if I could livestream a weekly concert. I didn’t know how a camera worked. I bought a little camera that my son is using now for astrophotography. We ended up using phones to shoot the livestream, and it was a big success. In the meantime, I walked around with that little camera and started seeing the world in a very different way.

When the Covid pandemic shut down our weekly show, that’s exactly what I needed: a different way to see the world. It was spring. I started going out at night with a light and shooting flowers, using the deep darkness as a frame.

I would never glorify suffering. It doesn’t make better art, and you don’t need to go looking for it to be creative. Suffering will come to you.

That said, shit is the best fertilizer.

These beautiful things got me through a lot of darkness. I made canvas prints and sold them. There was one that I never sold, and it sat and bugged me for a while. One day, I thought, that’s a nice piece of canvas. I could paint over it.

Maybe an artist is just someone who never remembers how hard it is to make things.

I watched YouTube videos. I bought five pigments in oil. Burnt umber. French ultramarine. Pyrrole rubine. Cadmium yellow. Titanium white. I built an easel out of scrap wood in my garage. I couldn’t figure out a clamp system, so I just screwed the canvas to the easel. I can’t remember where I got the brushes.

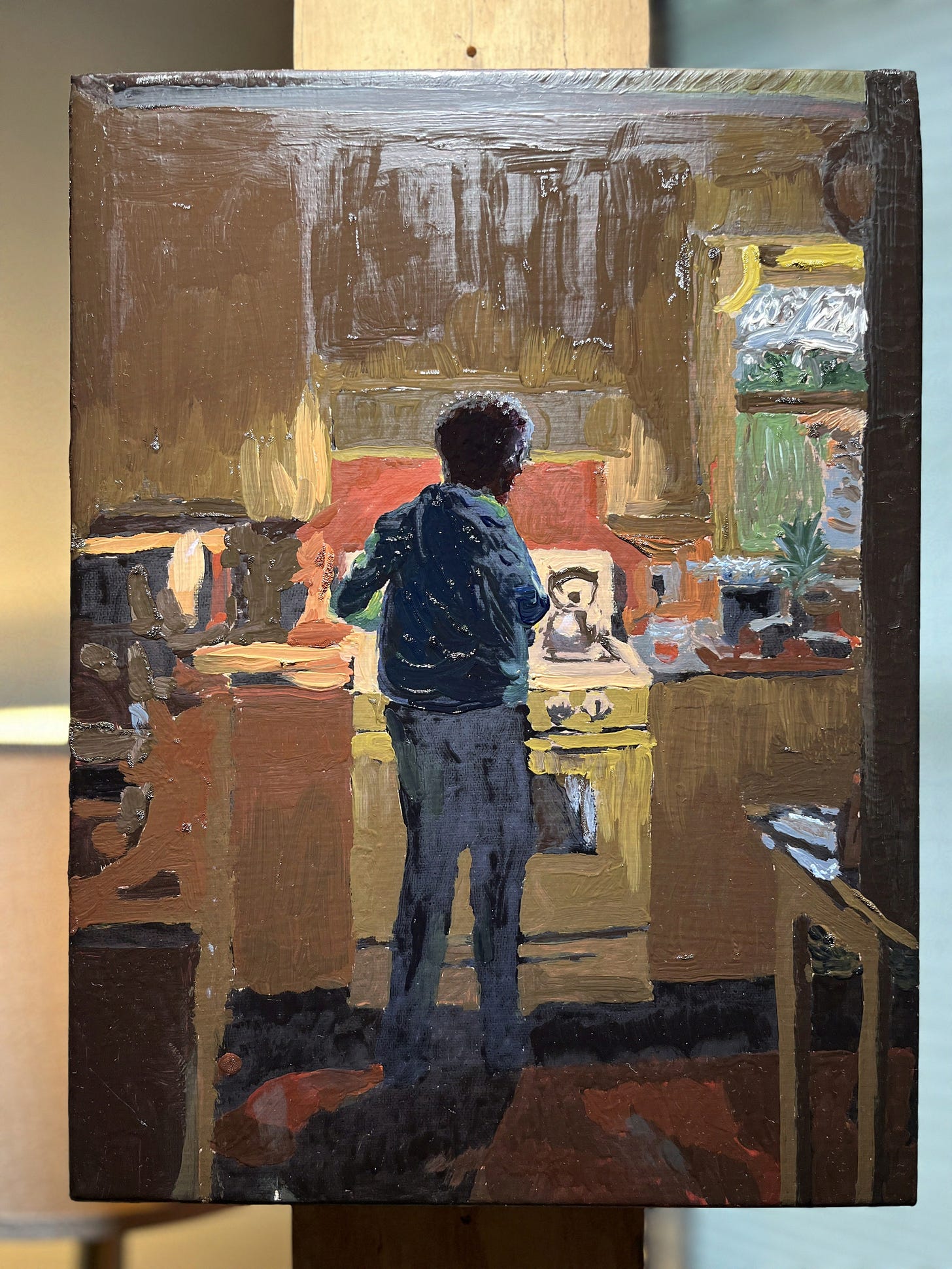

This is my first painting. Somewhere beneath the paint and gesso, there’s a pretty flower. It’s small, but it took about two years to finish. I didn’t know if I’d ever paint again.

Maybe you know that I’m studying physics. Six to eight hours a day, I do things like derive the velocity and acceleration of a three-dimensional position function, cross-multiply them, and divide by a cube of the velocity to get the curvature of motion.

I need to paint after a day like that. Music and writing are too familiar. I need to do something I don’t know how to do, something no one has to like, not even me.

I just finished my third painting, a rendering of the fading magnolia flower, dabbing away at night, listening to Russian composers, giving my brain a little spa day. To be clear, I have no idea what I’m doing. If you’d like to start oil painting, don’t listen to me. I’ve probably done everything wrong, but this is what I did.

I gessoed and toned the canvas years ago. That’s why it’s forty-ounce brown. The gesso seals the canvas and makes a smoother surface. The tone warms all the colors from beneath and makes it easier to see what I’m doing; everything looks too dark on a white canvas. I thinned out burnt umber and white with mineral spirits and gave it a couple of coats.

Looking closely, you’ll see I drew a grid on the canvas. I put a similar grid over the photo I used. That gave me some guidance.

I didn’t have any black paint. I made it by mixing burnt umber and French ultramarine. More burnt umber makes the black warm. More ultramarine makes it cool. I made my black on the warm side and painted the night behind the magnolia. Then I painted the shadows, the less shadowy shadows, and so on. Once I had a black and white (ish) version of the painting, I stopped.

The black parts were streaky. I waited a few weeks for it to dry to the touch and then filled it in, trying to mix precisely the same black as before. Then I waited another month for the whole painting to dry enough to paint over it again.

Titanium white dries as slowly as cotton underwear in Louisiana. After a month, the lighter parts were still not really dry. I went back in anyway and started painting colors. The burnt umber was miraculously just the color of an oxidizing magnolia flower, transparent enough to take the shape of the light and shadow beneath it.

Some greens are brown. Your brain likes to tell your eyes what to see. Your eyes have to tell your brain to shut up. That’s painting, in a nutshell.

Pure white is the last and hardest color of all. There’s not much of it, but it demands your attention. It has to be the color of the light, which is never precisely white. You can’t think your way into it. You can’t calculate the curvature of white. I make it. I scrape it and throw it away. I make it again. I try a few strokes. Ugh. I wipe it off and try not to ruin the painting as white gets into everything and never comes out, never dries, and will never be completely painted over.

As a songwriting teacher, one of the most common questions I got was, how do you know when you’re done? I’ll tell you a secret, the One Weird Trick that all professional artists learn.

There is no god of art. It’s done when you stop. The only way to keep going is to let go.

I sent a picture of it to a couple of friends. They said it was good. I cleaned my brushes. I walked by it for a few weeks. Lots of little things bugged me, and they kept bugging me. I was scared to touch it, but then I remembered that nobody has to like it, not even me. So I messed with it again and fixed all the little buggy things. My mom reminded me to sign it.

It’ll take at least a month to dry enough that I can move it safely, so it’s still screwed onto the easel in my living room. I don’t have anywhere else to put a wet painting. I’ve been walking by it, trying to see it accidentally as if I were a handyman here to fix a light switch. I still like it. It doesn’t bug me.

I started another. How hard could it be?

LOL.

Your fan,

Jonathan Byrd

Love this explanation of process. Love that you write your thoughts and share. In the dictionary of life there should be a picture of you defining “Renaissance Man.” Thank you.

Thank you for this sliver of awe in my day. Just what I needed.